With Christmas and the New Year over, it is time to turn your thoughts to planning for the tax year end.

While many parts of the tax landscape have been frozen, such as the personal allowance and most income tax thresholds, that does not mean you should ignore tax year-end planning as we approach 5 April. Among the areas to consider are:

· Pension contributions: The tax limits for pension contributions were eased at the start of the current tax year. You may now be able to make contributions for the first time in some years. But take care – just to complicate matters further, the rules will be changing yet again from 6 April 2024.

· Capital gains tax (CGT): Now is the time to review your investments and consider whether to realise gains up to your annual exemption. This is particularly important in 2023/24 as the exemption of £6,000 will fall to £3,000 in the next tax year.

· Individual savings account (ISA) contributions: Your annual ISA allowance is £20,000 (£9,000 for Junior ISAs), which cannot be carried forward. With the personal savings allowance frozen and the dividend allowance and CGT exemption both halving in 2024/25, the case for maximising ISAs has arguably never been stronger.

· Inheritance tax: Use your annual exemption (£3,000 per tax year) for 2023/24. If you have unused exemption from 2022/23 you can also gift this, but only after you have used the current year’s exemption.

· Marriage allowances: If you or your spouse/civil partner had income of less than the personal allowance in 2018/19 (£11,850), then you have until 5 April 2024 to claim the marriage allowance for that year (£1,190). A claim can only be made if the other partner was a basic rate taxpayer in that tax year. The same principle applies for 2019/20 onwards.

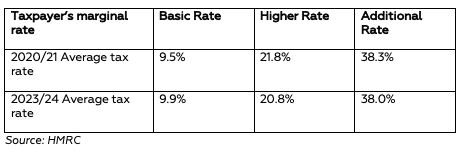

· Income planning: Frozen allowances and tax thresholds mean you could move from being a basic rate taxpayer now to a higher rate taxpayer in 2024/25. Similarly, from April you might be caught for the first time by the High Income Child Benefit Charge or personal allowance taper. Actions to limit the larger tax bill include bringing forward income into 2023/24 or transferring income-generating investments to your spouse/civil partner by 5 April.

As ever when it comes to tax, it is best to seek advice before taking any action.

Tax treatment varies according to individual circumstances and is subject to change.

The Financial Conduct Authority does not regulate tax advice.